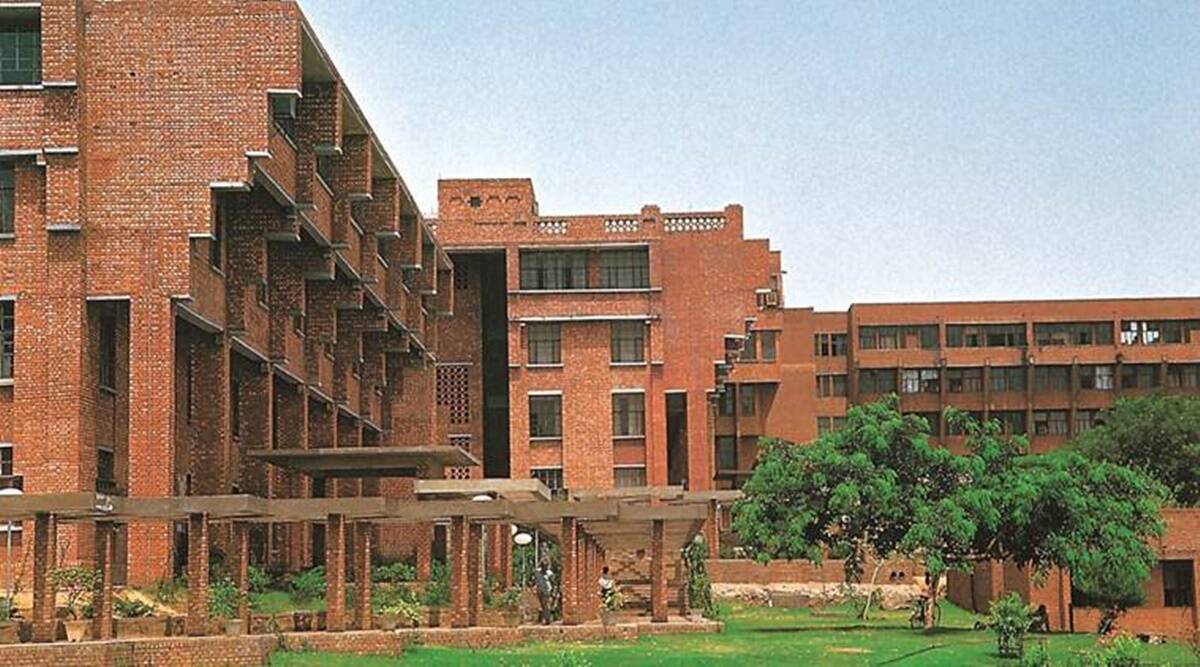

Jawaharlal Nehru University is once again at the centre of a campus churn, a decade after mass protests and open-air lectures defined its public image. This time, the flashpoint is not a slogan echoing through the Sabarmati lawns but an expanding web of surveillance measures that students and faculty argue are altering the character of one of the country’s most prominent liberal arts institutions.

Jawaharlal Nehru University is once again at the centre of a campus churn, a decade after mass protests and open-air lectures defined its public image. This time, the flashpoint is not a slogan echoing through the Sabarmati lawns but an expanding web of surveillance measures that students and faculty argue are altering the character of one of the country’s most prominent liberal arts institutions.Ten years ago, demonstrations led by Kanhaiya Kumar, then president of the Jawaharlal Nehru University Students’ Union, drew national attention. The 2016 protests, triggered by events on campus and the subsequent arrest of student leaders on charges of sedition, saw teach-ins, poetry readings and impromptu debates become symbols of a wider contest over dissent and academic freedom. The phrase “Azadi” moved from a campus chant to a national political flashpoint.

Today, students describe a different struggle. Administrative orders over the past few years have led to the installation of additional CCTV cameras across hostels and academic buildings, biometric attendance systems in certain centres, tighter access controls at campus gates and expanded monitoring of public gatherings. University officials maintain these steps are aimed at ensuring safety and administrative efficiency. Critics see them as part of a broader shift that has accelerated since 2016.

JNU’s administration has argued that surveillance infrastructure is standard across major universities and essential in a large residential campus that houses thousands of students. Officials have pointed to incidents of violence in the past, including clashes in 2020 that left students and teachers injured, as justification for heightened security. They say technology helps prevent vandalism, unauthorised entry and disruptions to academic schedules.

Student groups counter that the cumulative impact goes beyond safety. Members of the JNU Students’ Union and various political collectives say the proliferation of cameras and digital monitoring creates a climate of constant observation that discourages open political expression. Several faculty members have privately expressed concern that the ethos of informal debate, which once spilled from lecture halls into dhabas and hostel corridors, is harder to sustain under what they describe as an increasingly regulated environment.

Education analysts note that the changes at JNU mirror broader national trends. Across public universities, administrations have introduced biometric attendance, online proctoring, digital ID cards and expanded security networks. These measures have been framed as modernisation drives aligned with governance reforms and technological upgrades. At the same time, critics argue that such tools can be deployed to monitor dissent and curtail protest, particularly in politically sensitive institutions.

JNU’s transformation over the past decade has not been limited to surveillance. Admissions policies have shifted, including the replacement of certain entrance examinations with national-level tests. Faculty recruitment patterns, funding allocations and hostel rules have also evolved. Supporters of the administration argue that these changes have diversified the student body and standardised procedures. Opponents contend that they have altered the university’s social composition and ideological balance.

The campus that once hosted marathon debates under the open sky now requires prior permission for many public meetings. Posters are more tightly regulated, and student groups say approvals for seminars can be delayed or denied on administrative grounds. University authorities respond that guidelines are necessary to prevent disruptions and ensure that academic activity proceeds without obstruction.

Kanhaiya Kumar, who later entered electoral politics, remains a reference point in discussions about JNU’s political identity. His leadership during the 2016 protests turned him into a national figure and intensified scrutiny of the university. Since then, JNU has frequently been invoked in political discourse as a symbol either of vibrant dissent or of alleged ideological bias. That framing has shaped public perceptions and, according to some faculty, influenced policy decisions affecting the institution.

Security officials familiar with campus administration say the expansion of surveillance technology is not unique to JNU. They point to similar installations in universities in Delhi, Hyderabad and Kolkata. However, JNU’s history of high-profile protests gives these measures particular resonance. What might be seen elsewhere as routine security upgrades are interpreted on this campus through the prism of its legacy of agitation.

Students involved in the current mobilisation insist their campaign is not about reviving older slogans but about defending what they call the right to privacy and intellectual autonomy. Meetings have been held to discuss data protection, the legal basis for surveillance and the scope of university authority. Petitions have circulated questioning the storage and use of footage and biometric information.

Legal experts observe that public universities operate within a complex regulatory framework that balances security, administrative control and constitutional protections. The absence of a comprehensive data protection regime in higher education, they argue, leaves room for ambiguity over how surveillance data is handled and who has access to it.

Faculty members who have taught at JNU for decades describe a palpable change in atmosphere. Some say the intensity of ideological contestation has diminished; others argue it has simply moved online, into encrypted messaging groups and digital forums. The physical campus, once synonymous with spontaneous assemblies, now appears more orderly, though critics say that order has come at the cost of openness.