Supreme Court orders refusing bail to activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam in the 2020 Delhi riots conspiracy case have continued to shape legal and political debate, with the court maintaining that the allegations and statutory thresholds warranted prolonged custody while the trial process moved forward. The decisions, delivered in 2020, arose from petitions challenging lower court orders that had denied bail under provisions of the Unlawful Activities Act and other penal laws linked to the violence that engulfed parts of the capital earlier that year.

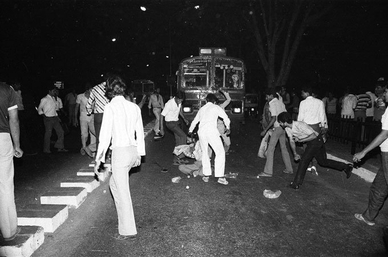

Supreme Court orders refusing bail to activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam in the 2020 Delhi riots conspiracy case have continued to shape legal and political debate, with the court maintaining that the allegations and statutory thresholds warranted prolonged custody while the trial process moved forward. The decisions, delivered in 2020, arose from petitions challenging lower court orders that had denied bail under provisions of the Unlawful Activities Act and other penal laws linked to the violence that engulfed parts of the capital earlier that year.The case stems from communal clashes in north-east Delhi that left more than 50 people dead and hundreds injured. Investigators alleged that the violence was the result of a premeditated conspiracy tied to protests against the Citizenship Act, contending that speeches, meetings and mobilisation efforts were part of a coordinated plan to disrupt public order. Umar Khalid, a former Jawaharlal Nehru University student leader, and Sharjeel Imam, a doctoral scholar, were arrested separately in 2020 and accused of playing roles in that alleged conspiracy.

In rejecting bail pleas, the Supreme Court accepted the prosecution’s argument that the accusations attracted the stringent conditions laid down in anti-terror legislation, which require courts to deny bail if, on a prima facie reading, the case diary and charge material disclose the commission of an offence. The bench emphasised that bail decisions at an early stage do not amount to a finding of guilt and that the evidentiary assessment would ultimately be undertaken during trial.

The court’s reasoning rested on the interpretation of statutory thresholds rather than an evaluation of witness credibility or the final merits of the prosecution’s case. It noted that Parliament had deliberately set a high bar for release in cases invoking national security and public order concerns, leaving limited discretion to courts once the threshold was crossed. This approach has been echoed in subsequent rulings involving similar statutes, reinforcing a jurisprudence that places legislative intent at the centre of bail determinations.

Both Khalid and Imam have consistently denied the charges, arguing that the allegations criminalise dissent and peaceful protest. Their legal teams have maintained that the prosecution relies heavily on selective readings of speeches and on statements of protected witnesses whose testimony, they argue, lacks corroboration. Civil liberties groups and sections of the academic community have also expressed concern over prolonged pre-trial detention, warning that delays risk undermining the presumption of innocence.

Government representatives, for their part, have defended the investigative process, asserting that the scale of the violence and the complexity of the alleged conspiracy necessitated stringent action. They have pointed to voluminous charge sheets, digital evidence and call records as justification for invoking special laws and opposing bail. Officials have also stressed that courts at multiple levels independently assessed the material before reaching their conclusions.

Legal scholars note that the Supreme Court’s 2020 stance has had a wider impact on how lower courts approach bail in cases involving special statutes. The emphasis on a prima facie standard, rather than a deeper scrutiny of evidence at the bail stage, has often resulted in extended incarceration while trials proceed. Critics argue that this shifts the balance too heavily in favour of the state, especially in cases where trials are protracted and convictions uncertain.

At the same time, supporters of the approach contend that it preserves the integrity of investigations in sensitive cases and prevents potential interference with witnesses or evidence. They argue that bail jurisprudence must account for the nature of alleged offences and the broader public interest, particularly when violence has resulted in loss of life and large-scale disruption.